Having dense breasts can put women at higher risk of breast cancer and make it more difficult to spot cancer on a mammogram, but many don’t realize it’s a significant risk.

Starting this week, all mammography reports and result letters sent to patients in the United States will be required to include an assessment of breast density. The US Food and Drug Administration’s final rule requiring that mammography facilities notify patients about the density of their breasts goes into effect Tuesday.

Breast density is a measurement of how much fibroglandular tissue there is in a woman’s breast versus fatty tissue. The more fibroglandular tissue, the denser the breast.

About half of women older than 40 in the United States have dense breast tissue, said radiologist Dr. Kimberly Feigin, interim chief of the Breast Imaging Service and head of the Breast Imaging Quality Assurance at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

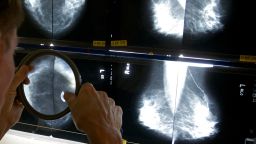

“We talk about breast density for two reasons. One is that breast density can make it more difficult to spot a cancer on a mammogram, because dense breast tissue – the glandular elements and connective tissue supporting elements – looks white on a mammogram and cancer also looks white on a mammogram,” Feigin said.

In other words, dense breast tissue can hide cancer on a mammogram since the tissue appears white on a mammogram, in the same way lumps and tumors appear.

“The second reason that breast density is important is because having dense breast tissue raises a woman’s level of risk of developing breast cancer,” Feigin said.

The new notification requirements don’t provide specific next steps for patients with dense breasts, but they recommend women talk with their providers to get a clearer sense of their individual risk and to determine a screening plan that’s right for them.

While it is recommended that all women get mammograms starting at age 40, some women with dense breasts may benefit from additional imaging options for breast exams, such as ultrasounds or MRIs.

Breast cancer survivor JoAnn Pushkin, 64, has advocated for more than a decade that there be a national requirement for women to be notified of their breast density. She said the new rule is a long time coming.

In her mid-40s, Pushkin noticed a lump in her breast but wasn’t particularly worried; she’d had a mammogram about eight weeks earlier that was normal.

But she still went back for a diagnostic mammogram, and the radiology technologist told Pushkin, “We didn’t see anything.”

Pushkin thought the technologist had mistaken her for another patient.

“It was a large facility with multiple waiting rooms, and I just assumed that she’d come back into the wrong room,” Pushkin said. “I said, ‘Oh no, I’m the lady with the lump so big I could feel it.’ And she told me, ‘Oh, you have dense breasts. That’s going to be a very hard find for us.’ And I remember sitting back and saying to her, ‘Wait, what?’ I didn’t even know how to make sense of that sentence.”

Even though Pushkin’s mammogram at the time did not reveal the lump that she felt, she did further testing and had an ultrasound performed of her breast.

“And there was the lump, clear as a bell,” Pushkin said. “It was determined to be breast cancer. Within 20 minutes, I learned I had dense breasts, I learned I had breast cancer, and I learned it had been missed because I had dense breasts.”

Pushkin was diagnosed at a later stage of the disease, and she said she underwent eight surgeries and eight rounds of chemo as part of her treatment.

“A few years later, I had a recurrence, and then 30 rounds of radiation. Now I have lymphedema, and all because it was detected at that later stage,” said Pushkin, who has testified before the FDA about breast density and co-created the website DenseBreast-info.org, which features resources on breast density.

“I feel that because I wasn’t told I have dense breasts, I was effectively denied the opportunity for an early-stage diagnosis.”

Standard for all people getting mammograms

So far, an estimated 39 states and the District of Columbia already have required some breast density information to be reported in mammogram result letters to patients, according to a tracker on the DenseBreast-info website. But the language in each state mandate can vary and does not always require providers to notify a patient about their risk, which is why advocates have pushed for a national requirement.

With the new FDA rule in effect, notifying patients about their breast density will be a blanket requirement nationwide.

“This will provide a uniform national standard now so that all women in all states, when they have a mammogram, will be told either that their breasts are dense or that they’re not dense,” said Dr. Wendie Berg, professor of radiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC, who co-founded and serves as chief scientific advisor of DenseBreast-info.org.

The new FDA changes require facilities to provide patients with information about their breast density and include specific language in the mammogram result letter to explain how breast density can influence the accuracy of a mammogram.

An example of a notification statement could be: “Breast tissue can be either dense or not dense. Dense tissue makes it harder to find breast cancer on a mammogram and also raises the risk of developing breast cancer. Your breast tissue is dense. In some people with dense tissue, other imaging tests in addition to a mammogram may help find cancers. Talk to your healthcare provider about breast density, risks for breast cancer, and your individual situation.”

Or a statement could be: “Breast tissue can be either dense or not dense. Dense tissue makes it harder to find breast cancer on a mammogram and also raises the risk of developing breast cancer. Your breast tissue is not dense. Talk to your healthcare provider about breast density, risks for breast cancer, and your individual situation.”

Understanding breast density

There are four categories of breast density provided on a mammogram report, ranging from mostly fatty to extremely dense, Berg said.

With mostly fatty breasts, “it’s very easy to see cancers, and these women are much less likely to develop breast cancer. The next category would be scattered fibroglandular density, which is actually the most common,” Berg said.

“And then heterogeneously dense, which can obscure masses – at least 25% of cancers are going to be missed in that category,” she said. “And then extremely dense would be the last category where at least 40% of cancers are going to be missed. And, if you compare a woman who has extremely dense breasts with someone who has fatty breasts, it’s actually as much as a four times higher risk of developing breast cancer.”

Based on her own family history of breast cancer and her breast density, 10 years ago, Berg said that she determined for herself that she had a 19.7% lifetime risk of developing the disease. Because of this, she insisted to her own physician that she undergo an MRI of her breasts to screen for cancer, instead of having only a 3D mammogram performed.

“The MRI showed a small invasive cancer that you can’t see on my own mammogram,” said Berg, who has since been treated for the disease.

“After that experience, I said, if we’re going to be telling women they have dense breasts, there needs to be a place for women to figure out if they meet criteria for an MRI or if they want to get an ultrasound and what to expect from these tests,” Berg said.

The FDA notes that in some people with dense breast tissue, other imaging tests in addition to a mammogram may help find cancers.

“But it doesn’t say any more than that. And then it ends with ‘talk to your healthcare provider,’” Berg said. “The guidelines are not as clear as they could be.”

Many women might not know whether to ask for additional imaging – such as with an MRI – or their doctor may not agree that they need it in some cases. Also for some cases, these options may not be covered by insurance.

“Knowledge is power, and all women can now have informed conversations with their medical providers about the screening plan that’s right for them based on factors influencing their personal breast cancer risk, including breast density,” Molly Guthrie, vice president of policy and advocacy at Susan G. Komen, said in a statement.

“We want everyone to know that dense breast tissue alone doesn’t necessitate additional imaging—it’s just one factor in breast cancer risk,” Guthrie added. “For those who do need imaging beyond a mammogram, out-of-pocket costs are often a barrier. That’s why we’ve been advocating for state and federal legislation to eliminate these expenses. We have the technology to detect breast cancer earlier and save lives, financial barriers shouldn’t stand in the way. It’s crucial for people to understand and have affordable access to the breast imaging they need based on their individual risk.”

Access to quality mammograms

The American Cancer Society has applauded the FDA’s new rule, saying it will reduce delays in diagnosis. It’s estimated that about 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime.

“The final rule will improve screening by addressing newer technologies, better enforcement of facility accreditation and quality standards, and enhance the reports that are provided to women and their physicians,” the ACS said in a statement last year.

The ACS said at the time that while the new changes can help reduce breast cancer mortality rates, more work still needs to be done to ensure all women receive access to high quality mammograms.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

According to the organization, “Black women are more likely to experience lower quality screening, contributing to the ongoing disparity” in breast cancer mortality among Black and White women.

A study published in 2022 found that the breast cancer death rate dropped by 43% within three decades, from 1989 to 2020, translating to 460,000 fewer breast cancer deaths during that time. When the data were analyzed by race, Black women were found to have a lower incidence rate of breast cancer versus White women, but the death rate was 40% higher in Black women overall.

“Either screening is important or it’s not. And if it’s important, it’s certainly more important for women who we know are at an elevated risk and for whom the mammogram is a compromised tool,” Pushkin said. “Notifying a woman about her beast density gives women the opportunity to advocate for themselves. How can you advocate for yourself in the absence of enough information to know that you need to?”